The UN Human Rights Council (HRC) in June 2007 completed its first year of activities having defined its principal institutional characteristics and its operating mechanisms. In this article, I propose to trace a brief history of this first year of the Council’s activities and suggest some forms of action that can be taken by non-governmental organizations.

In April 2006, the UN General Assembly approved the creation of the Human Rights Council (Council or HRC), making this body responsible for promoting universal respect for the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms. The same document that breathes life into the HRC emphasizes that peace, development and human rights constitute the three pillars of the United Nations system. It also recognizes that the work of the new Human Rights Council should be guided by the principles of universality, impartiality, objectivity and non-selectivity – in a clear reference to the criticisms leveled against the Commission on Human Rights (Commission), the body that preceded it.

In the former Commission, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) played an active and important role. There is no doubt that participation by NGOs in the new Council will continue to be essential, bringing to its attention local situations of human rights violations and monitoring the positions taken by its Member States. Neither is there any doubt that a stronger participation by NGOs from developing nations – the so-called Global South – will grow increasingly more necessary given, among other factors, the geographic composition of the HRC.

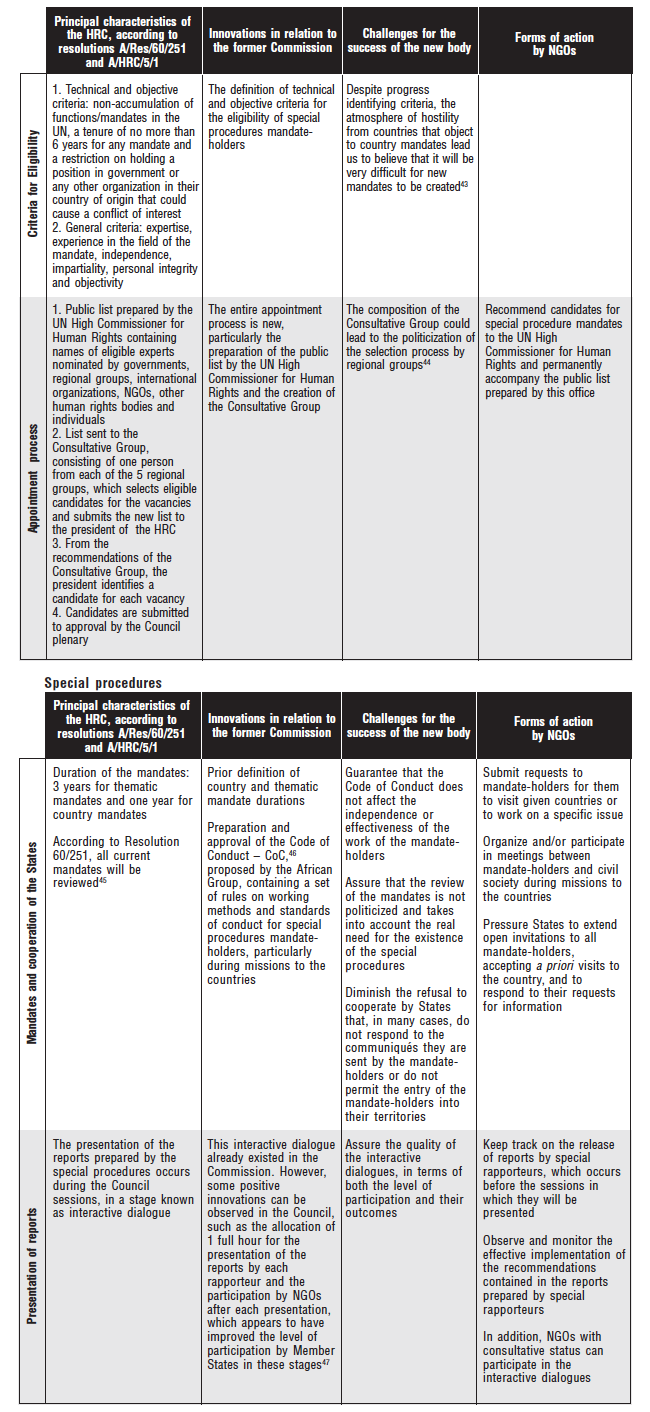

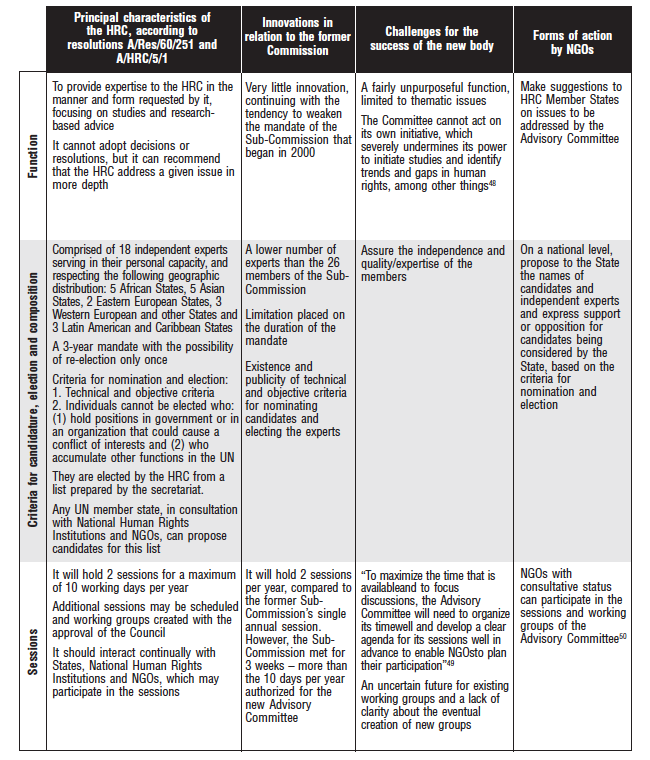

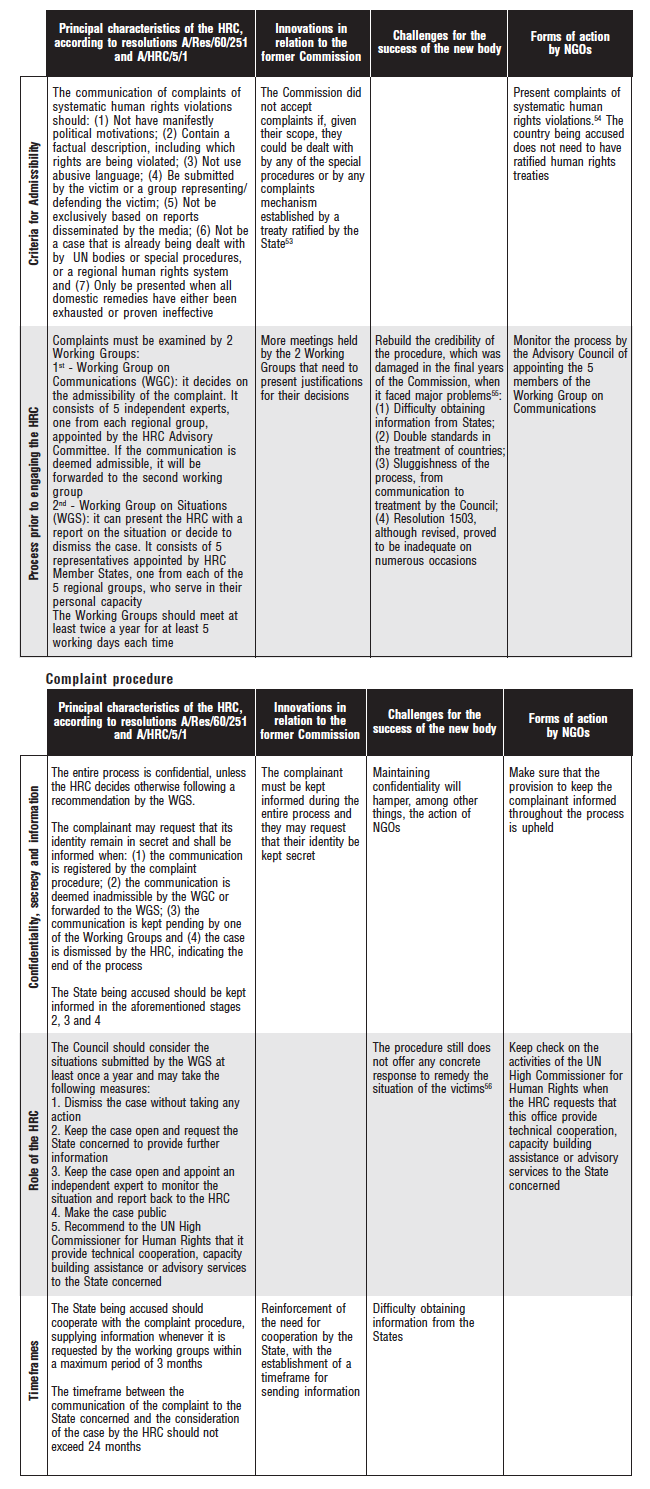

I propose, therefore, in this article: (1) to trace a brief history of this first year of the Council’s activities; (2) to put into context the importance NGO participation; and (3) to suggest some forms of action that can be taken by these organizations in the leading international body for the promotion and protection of human rights. In the third part of this article, the information has been compiled into tables, in an attempt to make it easier to read and to demonstrate that participation by NGOs in the Human Rights Council should be ongoing, both at the HRC headquarters in Geneva and with the governments at the capitals of their own countries.

The UN Human Rights Council completed its first year of activities in June 2007, during its fifth session. Established by UN General Assembly Resolution 60/251,3 the HRC replaced the sexagenarian Commission on Human Rights that was grappling at the time with a serious credibility crisis, accused by Non-Governmental Organizations and States of selectivity and excessive politicization in dealing with human rights violations around the world.

The HRC is today the principal international body for the promotion and protection of human rights; it is responsible for “promoting universal respect for the protection of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all, without distinction of any kind and in fair and equal manner”.4

The new body is comprised of 47 Member States elected by the General Assembly for a period of three years, respecting the following geographic distribution: 13 African States, 13 Asian States, 8 Latin American and Caribbean 13 Asian States, 6 Eastern European States and 7 Western European and other States.

Based in Geneva (Switzerland), the HRC must schedule no fewer than three ordinary sessions per year and it is also able to hold special sessions whenever necessary. In its first year, the HRC held five ordinary sessions and four special sessions to address the human rights situations in Palestine, Lebanon and Darfur. In addition, the Council also adopted: the International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance5 and the draft of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.6 Work also began on a draft Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Nevertheless, the primary focus of the HRC in these first twelve months was its own institution-building. According to Res. 60/251, the Human Rights Council had a year starting from its first session7 to “assume, review and, where necessary, improve and rationalize all mandates, mechanisms, functions and responsibilities of the Commission on Human Rights […]”.8

The HRC approved, in its fifth session, Resolution 5/1,9 the result of intense and tumultuous negotiations. The document sets out the principal characteristics of its agenda and program of work, methods of work and rules of procedure, universal periodic review mechanism,10 special procedures, advisory committee and complaint procedure.

In light of the intense negotiations and the clashes that took place during the institution-building phase, it is clear that the Human Rights Council is not immune to the problems that undermined the credibility of its predecessor. Indeed, there are signs that excessive politicization and the prevalence of interests other than the promotion and protection of human rights in the positions taken by Member States may well have been inherited from the Commission on Human Rights.

It is widely recognized that the active participation of NGOs in the former Commission on Human Rights was instrumental in the creation of international instruments, the approval of resolutions, the realization of studies and the creation of special procedures, among other things.11 Article 71 of the UN Charter authorizes the action of NGOs and makes the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) responsible for regulating this participation. In this context, ECOSOC Resolution 1996/3112 defines the principles and rights concerning formal participation by NGOs, its principal regulatory instrument being the concession of consultative status for civil society organizations.13

In the new Human Rights Council, the participation of NGOs is expressly guaranteed in Res. 60/251: “[…] the participation of and consultation with observers, including […] national human rights institutions, as well as non-governmental organizations, shall be based on arrangements, including Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31 […] and practices observed by the Commission on Human Rights, while ensuring the most effective contribution of these entities”.14

So far, NGOs have played an important role in the institution-building process of the HRC. In its first year, 284 NGOs participated in Council sessions, slightly less than in the former Commission.15

The role of NGOs in the Council is considered important to bring to its attention the reality in places where human rights violations are occurring and to contribute their own particular expertise. Furthermore, it is vitally important for NGOs to keep track on the positions taken by HRC Member States and observers, with a view to influencing them whenever necessary.

More participation by NGOs from the Global South is vital not only because most of the major fundamental rights violations occur in these countries, but also because the geographic composition of the HRC gives them numerical superiority. Together, African and Asian nations hold 26 seats on the Council, that is, more than 55% of the total. Adding the 8 countries from Latin America and the Caribbean, this figure rises to 72%. Many of these countries question the legitimacy of the action and the credibility of the information issued by NGOs that are not from their respective countries or regions.

However, NGOs from the Global South represent today just 33% of the 3050 NGOs that enjoy consultative status with ECOSOC16 and can, therefore, participate fully in the Council sessions.

There are countless challenges facing NGOs´ participation, foremost among them: (1) the difficult process of obtaining consultative status for those that do not already have it; (2) the high financial costs and the unavailability of staff to participate in the sessions in Geneva; (3) the lack of familiarity with the workings and procedure in the HRC; (4) the lack of access to information, including language barriers; and (5) the difficulty deriving any tangible benefits from this participation in the day-to-day work in their countries of origin.

Given these challenges, it is important to develop innovative forms of action. For example, the permanent engagement of NGOs from the Global South with their own governments at home is essential. All major foreign policy issues are decided on a national level, primarily in the Foreign Relations Ministries, including the positions to be taken by each country’s diplomatic missions and delegations in the Human Rights Council. It is imperative, then, for NGOs to call on their respective governments for more transparency and formal mechanisms to participate in the preparation and implementation of the guidelines that will govern their actions in the HRC.

It is also crucial for NGOs to coordinate strategies and develop joint initiatives for combined action within the HRC, both in Geneva and at home, to strengthen individual actions, maximize resources and share experiences.

There is no doubt that responsibility for the success of the HRC lies squarely with the countries that comprise the new body. Resolution 60/251 determines that the status of the Council within the hierarchy of the UN will be reviewed in 2011 and that it may become one of its principal bodies, on a par with the Security Council and the Economic and Social Council. Such a change in structure would, more than just being symbolic, demonstrate the interdependence between human rights, development and peace. This review will doubtless be a good indicator for evaluating the first five years’ work of the Council, which by then must prove itself effective in combating human rights violations, wherever they may occur.

Non-Governmental Organizations will be responsible for monitoring and pressuring States to place the protection of human rights and human dignity above any other interests. It is not too early to assert that NGOs have a lot of work ahead of them and that their engagement with the HRC is now more necessary than ever. This article proposes to contribute to the success of the initiatives taken by these organizations.

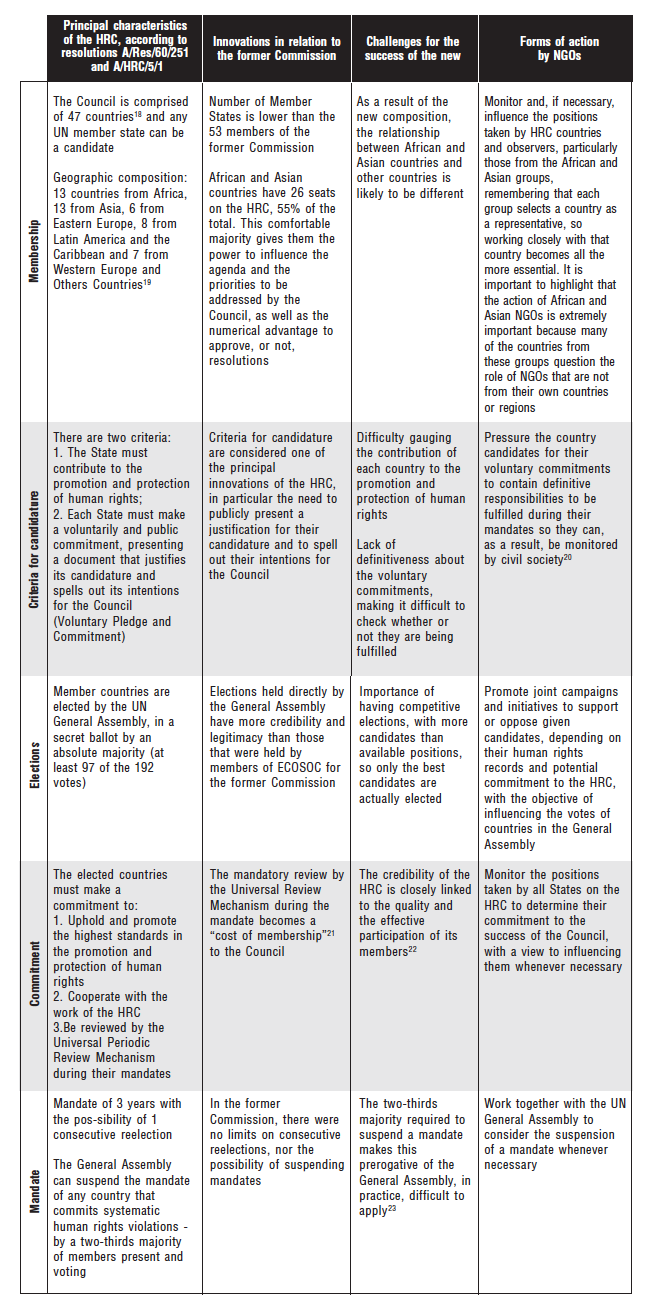

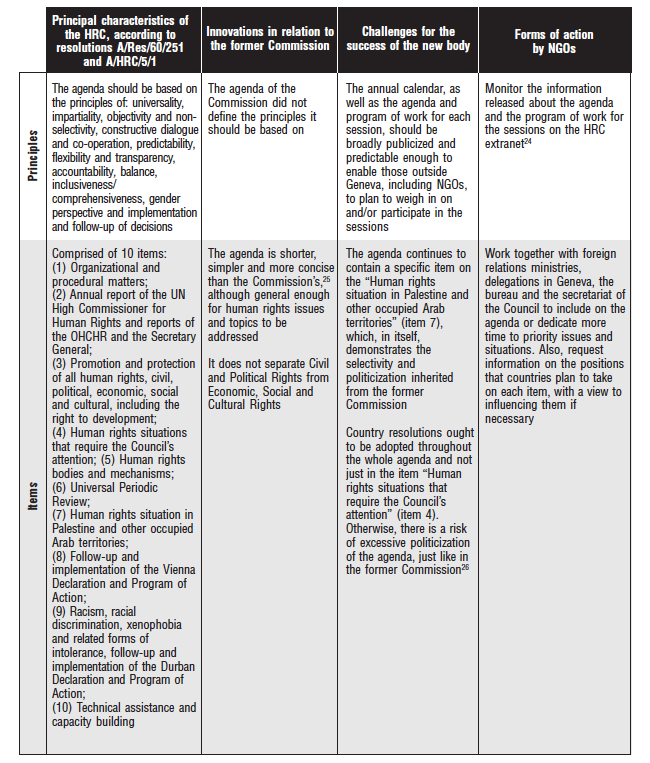

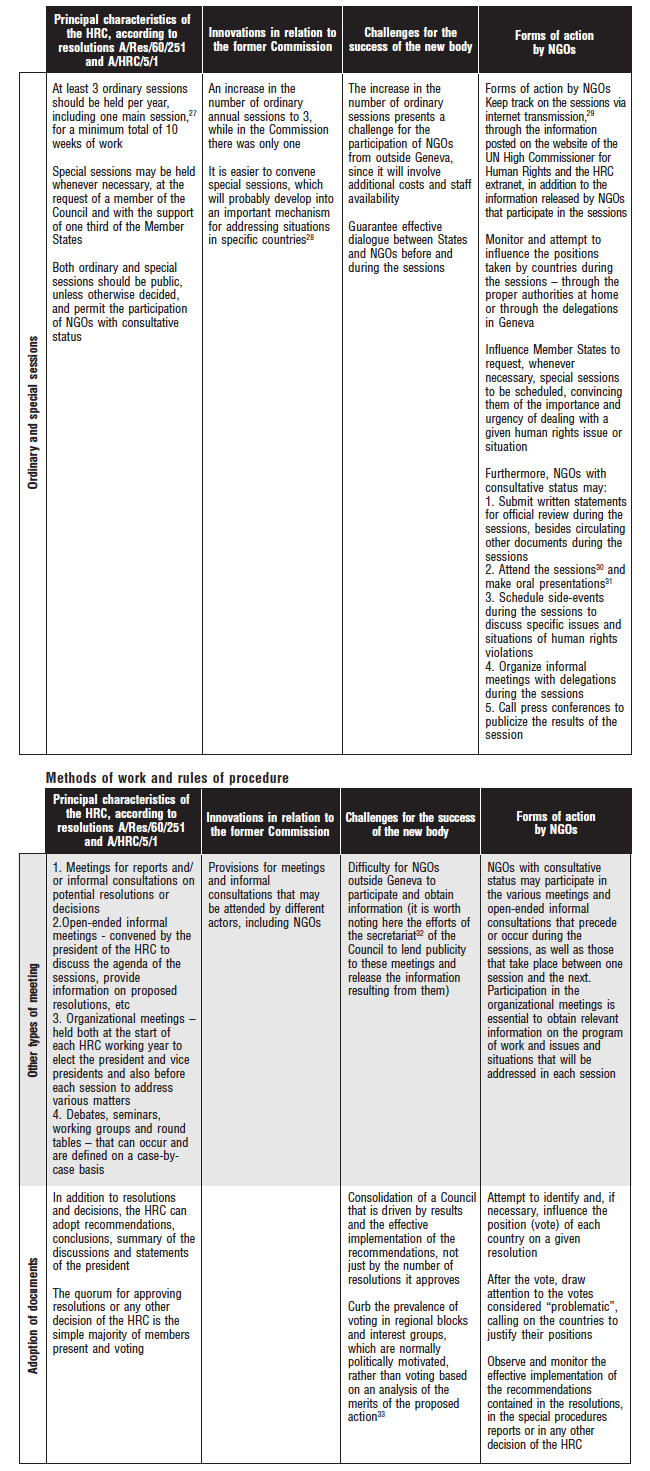

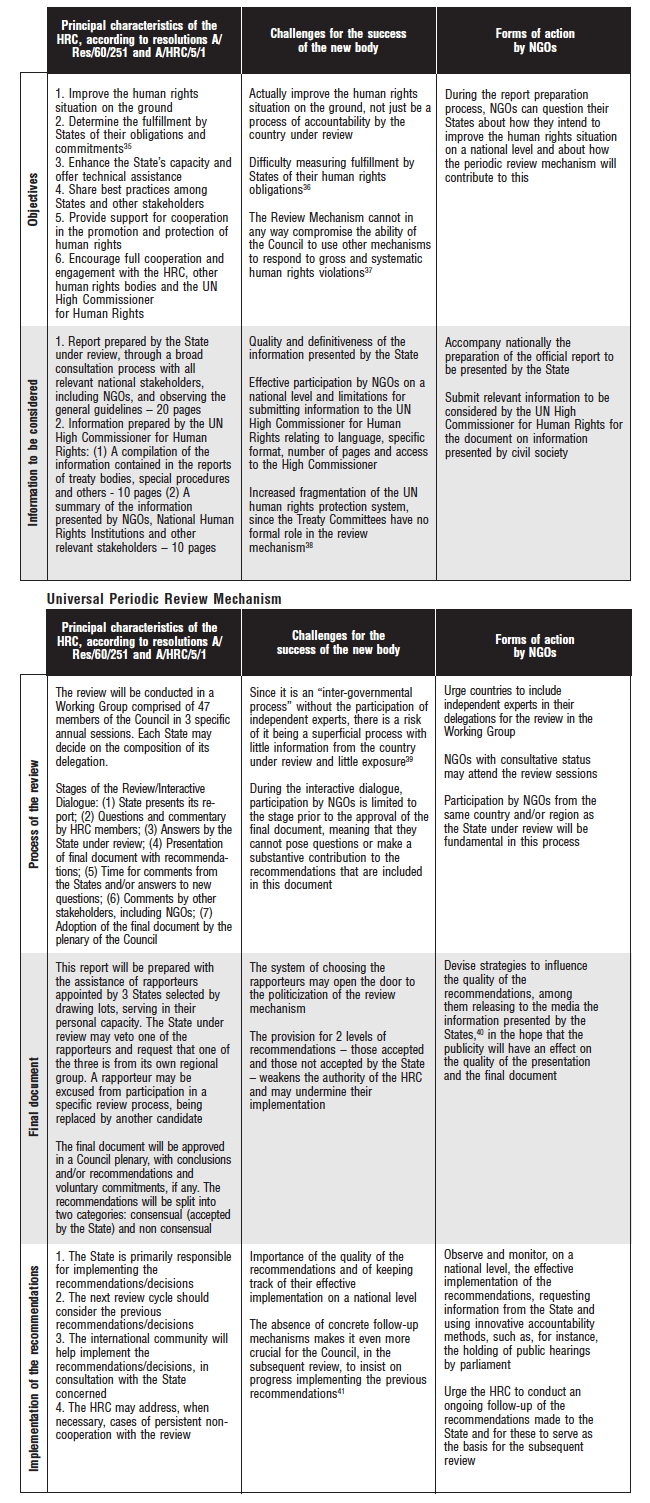

What follows is a description of the main characteristics of the Human Rights Council, the innovations in relation to the former Commission on Human Rights, some of the challenges the Council will face and suggestions for concrete forms of action by Non-Governmental Organizations in this new body.

It is worth pointing out that the suggestions on how NGOs can engage with the Human Rights Council are not limited to the strategies permitted only for NGOs that have consultative status with ECOSOC. These suggestions also place little importance on the distance between NGOs and the Council´s headquarters in Geneva.

The information contained in the following tables draws on General Assembly Resolution A/RES/60/251 and Human Rights Council Resolution A/HRC/5/1, as well as articles and reports on the topic that have been published to date.17 There are in all seven tables, in the following order:

1) Election and membership

2) Agenda and Program of Work

3) Methods of Work and Rules of Procedure

4) Universal Periodic Review Mechanism

5) Special Procedures

6) Human Rights Council Advisory Committee

7) Complaint Procedure

The electoral process is considered one of the major differences of the Human Rights Council in relation to the former Commission on Human Rights, since members are elected by the UN General Assembly and criteria have been included for presenting candidatures. Furthermore, the possibility exists in the Council to suspend the mandates of members that commit systematic human rights violations. The new composition of the HRC is also quite innovative, giving African and Asian countries a proportionally superior numerical force than they held in the Commission.

The agenda defines the items to be addressed by the Human Rights Council in its ordinary sessions and that are, therefore, incorporated into the Council’s program of work both for the whole year and for each individual session.

These define the general functioning of the Council’s ordinary and special sessions, other possible types of meetings and the quorum for approving resolutions, among other things.

Mechanism created by General Assembly Resolution 60/25134 that determines that all UN member states (universally) will periodically undergo a review process. The objective of the review is to determine the fulfillment by States of their international human rights obligations and commitments. It is considered the most innovative instrument of the Human Rights Council given the universality of coverage and the intention to combat the selectivity and double standards in responding human rights violations that existed in the Commission on Human Rights. The Council’s Member States undergo a review during their mandates and the review cycle lasts 4 years, meaning that 48 countries will be reviewed each year.

Since it is an entirely new mechanism, the table below does not contain a column on the innovations in relation to the former Commission on Human Rights.

This is the mechanism whereby special representatives and rapporteurs, independent experts and working groups examine, monitor and prepare reports on the situation of human rights: (1) in specific countries (country mandates) or (2) on specific issues (thematic mandates).42 During the institution-building process, special procedures were one of the most controversial topics, with questions raised about the need for their existence and an attempt to weaken this system by various member states.

This committee is a subsidiary body of the Human Rights Council that replaces the former Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection Human Rights (Sub-Commission). Its job is to provide advice on thematic issues of interest to the Council.

Procedure through which individuals and NGOs can file complains of systematic human rights violations52 that occur in any part of the world and under any circumstances.

1. I am grateful to Thiago Amparo and Camila Asano for their help compiling the information contained in this article and for their tireless work with the UN Human Rights Council as staff members of Conectas Human Rights.

2. Former Secretary General of the UN, in a speech at the inaugural session of the Human Rights Council, “The Secretary General Address to the Human Rights Council”, on 19 June 2006,

3. General Assembly, Human Rights Council, Resolution A/RES/60/251, 3 April 2006, available at <http://www.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/A.RES.60.251_En.pdf>, last access on 30 August 2007.

4. Ibid.

5. UN, International Convention for the Protection of all Persons From Enforced Disappearance, not yet in force, available at <http://www.ohchr.org/english/law/disappearance-convention.htm>, last access on 15 September 2007.

6. UN, Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (draft), Res. 2006/2, 2006: available at <http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/hrcouncil2-2006.html>, last access on 12 September 2007.

7. The first session of the Human Rights Council occurred from 19-30 June 2006 in Geneva.

8. General Assembly, Human Rights Council, Resolution A/RES/60/251, 3 April 2006,Paragraph 6.

9. Human Rights Council, Institution-building of the United Nations Human Rights Council, Res. A/HRC/5/1, 18 June 2007, available at <http://www.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/5session/reports.htm> last access on 10 September 2007.

10. Created by Res. 60/251 of 3 April 2006, the General Assembly requires all UN Member States to submit to a periodic review to determine the fulfillment of their international human rights obligations and commitments.

11. International Service for Human Rights (ISHR) and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, A New Chapter for Human Rights – a handbook on issues of transition from the Commission on Human Rights to the Human Rights Council, Geneva/Switzerland, June/2006, p.88, available at , last access on 21 August 2007.

12. UN, ECOSOC, Resolution 1996/31 – Consultative Relationship between the United Nations and non-governmental organizations, 25 July 2006, available at <http://www.un.org/esa/coordination/ngo/Resolution_1996_31/index.htm>, last access on 30 September 2007.

13. See the criteria for obtaining consultative status with ECOSOC in: ECOSOC, How to obtain Consultative Status with ECOSOC, available at <http://www.un.org/esa/coordination/ngo/howtoapply.htm>, last access on 11 September 2007.

14. General Assembly, Human Rights Council, Resolution A/RES/60/251, 3 April 2006, Paragraph 11.

15. In R. Brett, Neither Mountain nor Molehill – UN Human Rights Council: one year on, Quaker United Nations Office, Geneva/Switzerland, August 2007, p. 13, available at , last access on 10 September 2007.

16. European NGOs represent 37% and North American NGOs 29% of the total. Data available in ECOSOC, Number of NGO’s in Consultative Status with the council by Region, 2007, available at <http://www.un.org/esa/coordination/ngo/pie2007.html>, last access on 12 September 2007.

17. Special thanks to three bibliographic references that were crucial in developing this article: International Service for Human Rights (ISHR) and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, A New Chapter for Human Rights – a handbook on issues of transition from the Commission on Human Rights to the Human Rights Council, op. cit; Y. Terlingen, “The Human Rights Council, A New Era in UN Human Rights Work?”, Ethics & International Affairs, v. 21, number 2, 12 June 2007 and M. Abraham, Building the New Human Rights Council – outcome and analyses of the institution-building year, Geneva/Switzerland, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, August 2007, available at <www.fes-globalization.org/geneva>, last access on 11 September 2007.

18. For a list of current members of the HRC, see Membership of the Human Rights Council, available at <http://www.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/membership.htm>, last access on 30 August 2007.

19. In the Commission on Human Rights, the geographic composition was: 15 African countries, 12 Asian, 5 from Eastern Europe, 11 from Latin America and the Caribbean and 10 from Western Europe and other countries. Both in the Commission and in the Council, the geographic division is reflected in 5 “regional groups” that work together more or less cohesively: African group, Asian group, Eastern Europe group, America and the Caribbean group (GRULAC) and Western Europe and Others group (WEOG).

20. On this topic, see the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative report, Easier Said than Done – a report on the commitments and performances of the Commonwealth members of the UN Human Rights Council, 2007, available at , last access on 15 September 2007.

21. R. Brett, op. cit., p. 5.

22. Ibid., p.15.

23. C. Villan Duran, “Lights and Shadows of the new United Nations Human Rights Council”, Sur – International Journal on Human Rights, no. 5, year 3, São Paulo/Brazil, 2006, p.11, available at , last access on 15 September 2007.

24. The Council’s official documents are available on its official website <http://www.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/> or its extranet, <http://portal.ohchr.org/> (login: hrc extranet; password: 1session).

25. Commission on Human Rights, Resolution 1998/84, 24 April 1998, available at <http://www.unhchr.ch/Huridocda/Huridoca.nsf/TestFrame/a2d51307fc6f017680256672004dd8c2?Opendocument>, last access on 2 September 2007.

26. International Service for Human Rights (ISHR) and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, op. cit. p.26.

27. Main Session, held annually in March, during which the High Level Segment will occur with the participation of ministers of state and ambassadors of Member States.

28. Y. Terlingen, op. cit.

29. The sessions of the Human Rights Council are broadcast live on the internet at <http://www.un.org/webcast/unhrc/index.asp> (webcasting), last access 23 August 2007.

30. The only way NGOs without consultative status can participate in the sessions of the HRC is by joining delegations of NGOs with consultative status, when authorized by them and acting on their behalf.

31. After the interactive dialogue and debates, each accredited NGO is given 3 minutes to make their oral presentation.

32. The Office of TheHigh Commissioner for Human Rights acts as the secretariat and it is responsible for translating, printing, circulating and preserving all official documents of the HRC.

33. A New Chapter for Human Rights – a handbook on issues of transition from the Commission on Human Rights to the Human Rights Council, op. cit., p. 28

34. General Assembly, Human Rights Council, Resolution A/RES/60/251, 3 April 2006, Paragraph 5.

35. According to Resolution A/HRC/5/1, the basis of the review will be the: (1) UN Charter, (2) Universal Declaration of Human Rights, (3) Conventions and covenants to which the State is party, (4) Voluntary pledges and commitments made by States – including those undertaken when presenting their candidatures for election to the HRC, (5) Applicable international humanitarian law.

36. C.Villan Duran, op. cit.

37. International Service for Human Rights (ISHR) and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, op. cit., p.84

38. C. Villan Duran laments that no permanent institutional working relations were established between the Council and the Treaty Committees, in C. Villan Duran, op. cit., p. 15.

39. According to P. Hicks (Human Rights Watch), “The possibilities of using these reviews to expose violations and push for change are vast, but the spirit of ‘protect our own,’ which has limited action by the council so far, could infect these reviews as well,” in P. Hicks, “Don’t Write it Off Yet”, International Herald Tribune, 21 June 2007, available at , last access on 22 August 2007.

40. M. Abraham, op. cit., p.40.

41. See also Amnesty International, “Conclusion of the United Nations Human Rights Council’s institution building: Has the spirit of General Assembly resolution 60/251 been honoured?”, 20 June 2007, available at Index: OIR 41/015/2007 (Public), last access on 15 August 2007.

42. See the list of current special procedure mandate-holders (thematic and country) at <http://www.ohchr.org/english/bodies/chr/special/index.htm>, last access 15 September 2007.

43. M. Abraham, op. cit., p. 29.

44. Ibid., p. 5.

45. However, the special procedure mandates for Cuba and Belarus were eliminated in the 5th Session of the HRC, as a result of political pressure from the two countries.

46. NGOs were categorical and persistent in their attempt to convince the African group there was no need to prepare a code of conduct for special procedures mandate-holders, fearing that this code could limit the autonomy and independence of the system. Human Rights Council, Resolution A/HRC/5/L.3/Rev.1 (Code of Conduct), 18 June 2007

47. R. Brett, Neither Mountain nor Molehill – UN Human Rights Council: one year on, op. cit., pp 5 and 9.

48. M. Abraham, op cit., p.17.

49. Ibid., p. 18.

50. In the Sub-Commission, it became common practice for NGOs without consultative status to participate in the Working Groups, which could lead to the same thing happening in the new Advisory Committee.

51. The complaint procedure of the former Commission on Human Rights was based on ECOSOC Resolutions 1503 (XLVIII), available at http://www.unhchr.ch/huridocda/huridoca.nsf/(Symbol)/1970.1503.En?OpenDocument, and its revised version, Resolution 2000/3, of 19 June 2000, available at http://www.unhchr.ch/huridocda/huridoca.nsf/(Symbol)/E.RES.2000.3.En?OpenDocument, last access on 12 September 2007. The new complaint procedure draws on various characteristics of both these resolutions.

52. Individual cases are not accepted.

53. M. Abraham, op. cit., p. 21.

54. These should be submitted to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, even by NGOs without consultative status with ECOSOC.

55. International Service for Human Rights (ISHR) and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, op. cit., p.66

56. Ibid., p.65.